Once upon a time, this was the first and only individual professorial homepage on the website of the European University Institute. The Institute’s first webmaster Sieglinde Schreiner asked Bo Stråth to create it as a test case, and they began the experiment together. The late James Kaye, a Ph D researcher on Stråth’s team, contributed the page’s single photo, which pictured Stråth outside the Institute, driving his Saab on a curve, looking both forwards and backwards in the rearview mirror. It was an attempt to create an image that encapsulated the historian’s craft. The time was at the end of the 1990s. The photo remains on the site.

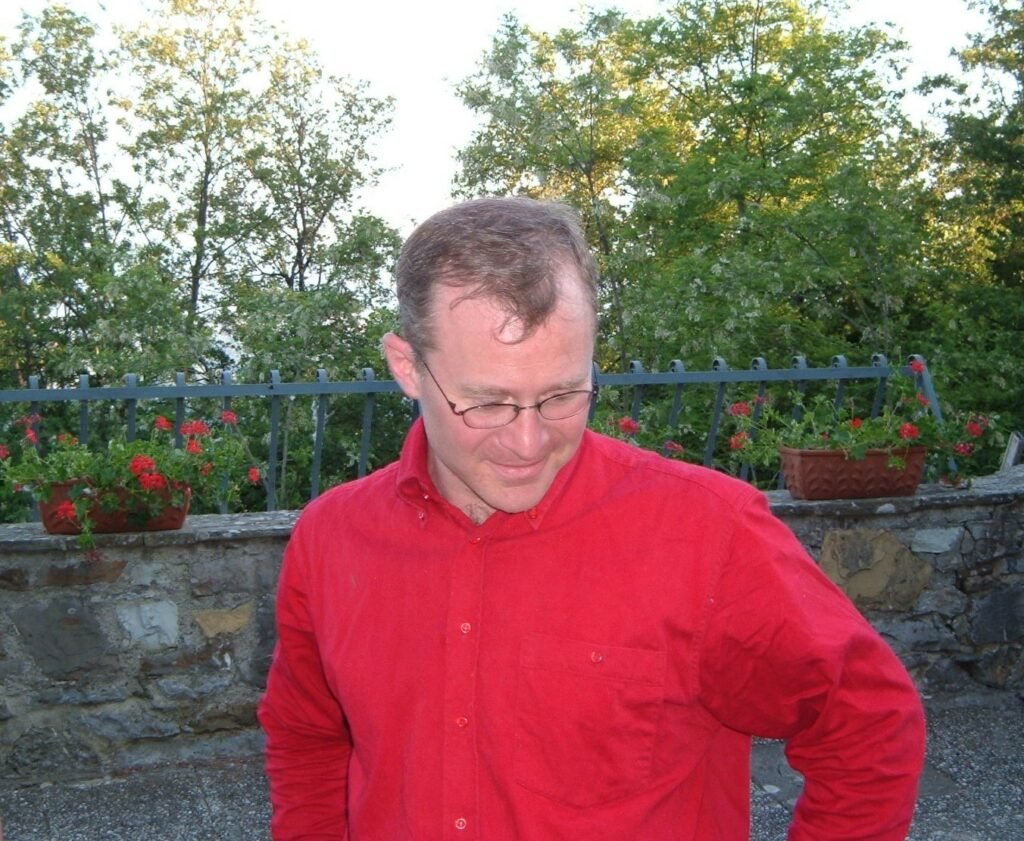

To the left, the late James Kaye at Pratolino around 2005.

The page developed and expanded over the time Stråth spent at the EUI. In 2007, when he moved to Helsinki University, his son Johan did a great job finding a new server, moving the page there and giving it a new design. In that context, Angela Schenk made the second photo of Stråth on the homepage until 2023, which still remains as the front photo. The new home page was like that in Florence: a cumulative diary about Stråth’s activities. However, the Europe 1815-1914 project had its own home page on the Helsinki University server and was deleted a few years after its closure in 2014. Part of the diary thus went lost.

However, the bigger problem with the homepage after 2014 was another. As a cumulative diary, it was easy to find what was going on and coming up but less so to search for events in the past. Designed as a diary with little or no inflow of new information, it grew increasingly irrelevant and hard to navigate. The history was still there for anyone to read, but the page became ever more a relic. The only way it could function was as an archive. However, to serve as an archive, it was, with the diary design, like looking for books in a library without a proper catalogue.

As an archive, the justifying function of the homepage would be to document the practices of knowledge production, which might have some public interest. Making the diary into an archive with a key would mean a fundamental redesign. After seriously considering deleting it, Stråth decided in 2023 to redesign, update and relaunch it. In the Palatinate, where he lives, he discovered, in the town of Landau, Marc Depuhl, who has made a heroic effort to excavate the old material and organise it afresh. His achievement inspired Stråth to supplement the information with new photos, explanatory notes, and comments. Friends and colleagues also contributed material, while Johan Stråth helped on the technical side. Angela Schenk revived memories where gaps had grown. The new page meant a new categorization, interactive references between and within the categories, and many new photos.

The homepage, as a documentation of the practices of knowledge production, is based on the argument that not only the academic/epistemological dimension of knowledge is relevant for understanding how knowledge is produced. Networks and friendships, less friendly contacts, too, of course, and contents and participants of meetings, seminars, conferences, etc, are relevant production factors determining the final product. Henning Trüper masterly epitomizes the argument in Topography of a Method (2014). Of course, ordering the homepage in this way reflects a personal need to summarize, order, and take stock of a professional life coming to an end. What was important? What was successful, and what was less so or failed? What could have been done differently? These questions and their answers are not explicitly addressed, but they implicitly guided the reorganisation of the homepage. This is to say that, to a certain degree, the homepage is a monologue or dialogue of Stråth with himself.

One question remained. How should Stråth present himself on the page? In the first- or third-person singular? Any choice seemed problematic. ‘I’ might elide with ‘we’ and end up sounding the royal we. Or it might end up in a monologue with himself. The third person ‘he’ probably provides more distance but provokes the question of whether he should be Bo or Stråth. He discussed the issue with Tim Luscombe, who has washed several Stråth texts over the past few years. As a native Swede, having lived through the radical ‘Du’ reform of the late 1960s, but now living in Germany where that experience has encouraged him to offer Du over Sie too easily, this question was vexed. In the end, his German re-training in old-fashioned reverence, not to mention that from the very start of the homepage, he appears as ‘Stråth’, made his choice for him. Other factors also impinged. The aim of the homepage, whose subject is the documentation of the practice of knowledge production, is not to chat self-indulgently about the state of the weather, the world or this year’s wine but to offer something of more general interest, something a little elevated, a bit slower and inviting to reflection than the fast pucks in social media. Ultimately, the appearance of Stråth as Stråth gives him a certain distance, particularly from himself, but also more generally in public conversation and debate, where the boiling emotions in social media have destroyed all distance, threatening values like decency and dignity. This distance allows him to emphasize the humble individual in the third person over the royal we in the first person, singularis humilis over pluralis majestatis.The Journey.